Reason is important and should play a large role in our lives. After all, we enjoy achievements of technical and other kinds that are largely thanks to reason. Many of the forms of magic is also reasonable, if not entirely scientific. However, the aspect of magic closest to me is its relation to the irrational and the imaginary. The latter two are important, even if we assume that everything can be explained on a purely rational basis. In fact, one of the major underlying theme of current social problems , I think, is the inability to deal with the irrational. On the one hand this means that there is an irrational aspect of the human existence (and again, it may as well be described by rational means), an important one, which does not want to follow rules and laws. Instincts, hidden desires and the sort, some of which are simply banned, ignored, maybe punished, until they possibly return in a monstrous form (to borrow an expression used to describe Gothic horror). On the other hand, there is a not entirely unrelated, but rather more purely aesthetic or atmospheric aspect, that I merely refer to as poetry. This latter aspect is the one that I wanted to deal with here, solely in the framework of fiction.

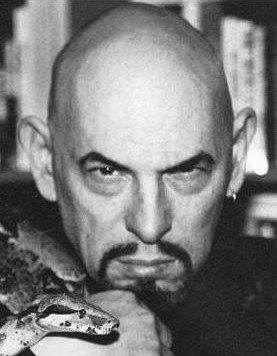

It is the appeal of magic, which is magical. Whether it is an an atmosphere of ancient wisdom and sorcery or enchantment by the beauty of something, it is the appeal that I like and not whether it works in the physical world or not. In this sense it can be a very useful, in a way surreal craft to approach real and unreal in fiction. There are plenty of examples. Lovecraft's myth and its deadly book the Necronomicon, that so effectively embodies the occult and fearful, since we never can read it but know that whoever did, went crazy or worse. There is Polanski's "Ninth Gate" which takes us to the realm of old books, very rare and containing hidden knowledge only to the initiated. There is Burton's "Sleepy Hallow", an adventure in the world of Gothic and magic.

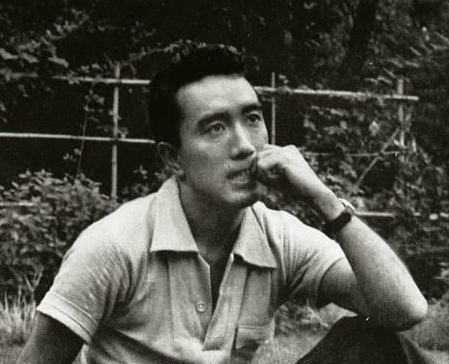

However, I wanted to show a few clips from Miyazaki's "Howl's Moving Castle" as ones I especially like. It is the story of a magician, Howl, who gave his heart to a demon, and a young girl, Sophie, who is turned into an old woman by a witch. The country is in war, which Howl finds mad, and sometimes interferes with. He is also hiding from his teacher, the royal sorceress, Saliman, who wants to put a control on magical practices in the country. The first scene shows the discovery of a malicious magic spell. I merely post it because it has the appeal I was referring to. The second is the confrontation scene with Saliman, where Sophie, now as an old woman, poses as Howl's mother. I love the idea of danger hidden behind such innocent looking things as that chanting... Like in other works of Miyazaki, there are lots of surreal images, events and characters, which somehow look familiar but yet which would be hard to explain. In a way they are also about reality as experienced by the viewer, and yet things just "melt together" as if in a dream. Howl is especially a good example of this sort of magic...

It is the appeal of magic, which is magical. Whether it is an an atmosphere of ancient wisdom and sorcery or enchantment by the beauty of something, it is the appeal that I like and not whether it works in the physical world or not. In this sense it can be a very useful, in a way surreal craft to approach real and unreal in fiction. There are plenty of examples. Lovecraft's myth and its deadly book the Necronomicon, that so effectively embodies the occult and fearful, since we never can read it but know that whoever did, went crazy or worse. There is Polanski's "Ninth Gate" which takes us to the realm of old books, very rare and containing hidden knowledge only to the initiated. There is Burton's "Sleepy Hallow", an adventure in the world of Gothic and magic.

However, I wanted to show a few clips from Miyazaki's "Howl's Moving Castle" as ones I especially like. It is the story of a magician, Howl, who gave his heart to a demon, and a young girl, Sophie, who is turned into an old woman by a witch. The country is in war, which Howl finds mad, and sometimes interferes with. He is also hiding from his teacher, the royal sorceress, Saliman, who wants to put a control on magical practices in the country. The first scene shows the discovery of a malicious magic spell. I merely post it because it has the appeal I was referring to. The second is the confrontation scene with Saliman, where Sophie, now as an old woman, poses as Howl's mother. I love the idea of danger hidden behind such innocent looking things as that chanting... Like in other works of Miyazaki, there are lots of surreal images, events and characters, which somehow look familiar but yet which would be hard to explain. In a way they are also about reality as experienced by the viewer, and yet things just "melt together" as if in a dream. Howl is especially a good example of this sort of magic...