It is not uncommon for writers of detective fiction that mystery and/or adventure penetrates their own lives. In 1947, Mary Roberts Rinehart, whose work spawned the detective fiction stereotype "The Butler Did It!", was the target of a murder attempt, though it was not the butler who did it, but the cook apparently jealous of the butler. In 1926, Agatha Christie disappeared for eleven days, apparently as a result of a marriage crisis, though the precise reasons are still disputed. An interesting case for detectives of literary research is that of Edward Lytton Wheeler, whose date of death may be established among others from the change of style in his Deadwood Dick series which went on ghost-written by someone else long after his estimated time of death.

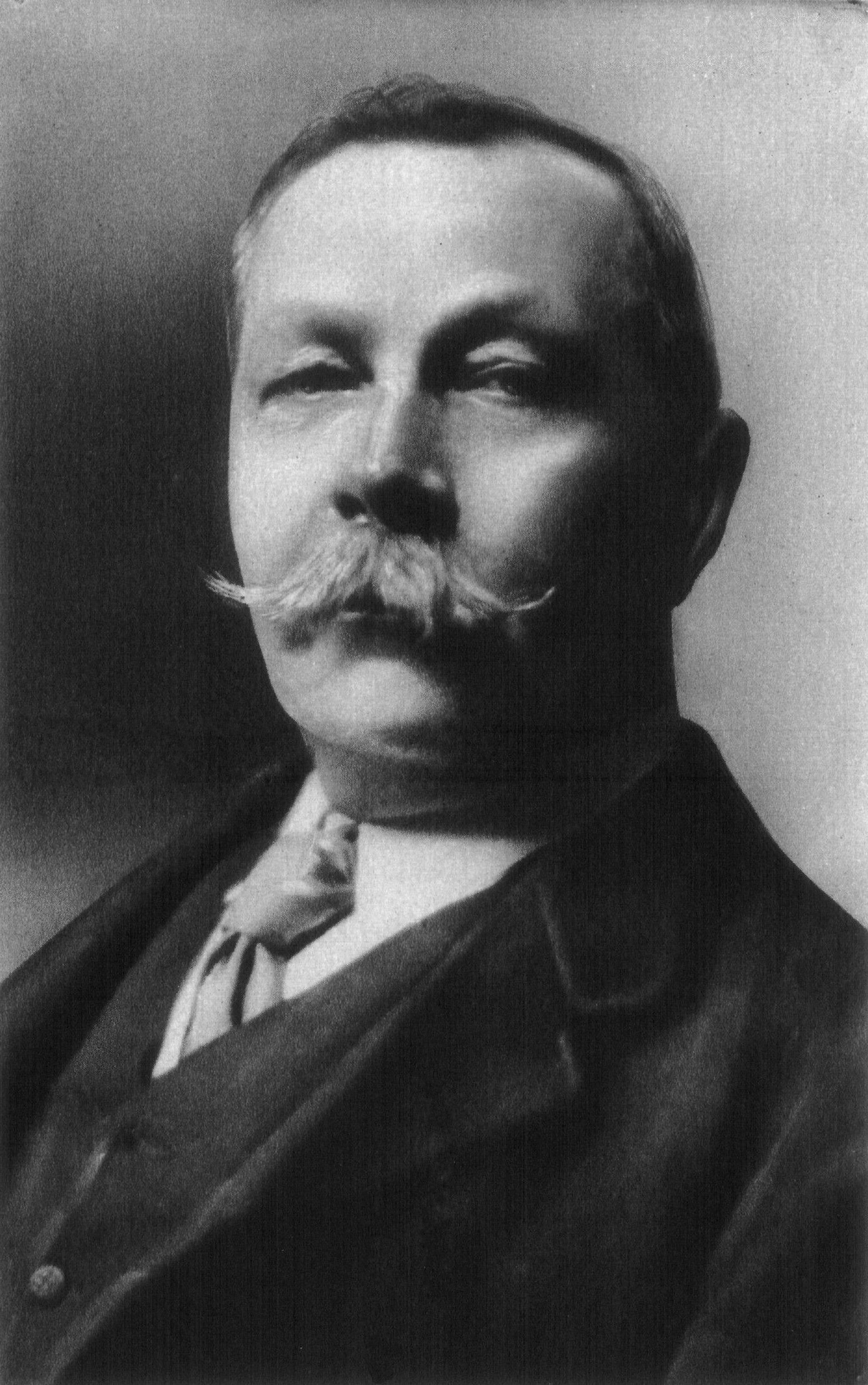

Nevertheless, it appears that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of Sherlock Holmes, was the one writer who actually investigated a case in a manner worthy of the reputation of his creation. He did not, as Dickens or Balzac did before him, join well-known policemen of his era to learn more of the world of crime. He read the published accounts of a case which made him investigate it. In 1903, several animals were left to bleed to death from a hallow cut to their abdomen by an unknown perpetrator in Great Wyrley in England. The police, under pressure arrested a young solicitor, George Edalji. The person of Edalji, being of Indian descent, fitted in nicely with the local belief that the killings were some sort of a religious ritual, although Edalji himself was Anglican, his father being a vicar. Various pieces of evidence were produced, including a bloody razor as a weapon, a muddy boot, and a shirt with horse hair on it originating from the last animal killed. Threatening letters that were sent to many households at the time also pointed towards him, as he had been considered a suspect in an earlier case of such letters, a suspicion probably motivated by racial prejudice without reason or evidence mentioned. The fact that witnesses swore that they had seen him as one such letter arrived to the Edalji house were ignored in favour of the theory that he wrote those letters to himself. Edalji was sentenced to seven years of hard labour. With his arrest, the letters and killings did not cease. Petitions were submitted for his release which occurred after three years later without specifing the reason. Although free, he could not practice his profession as a convicted criminal. This is when he decided on stating his case in public, which eventually arouse the attention of Conan Doyle.

Conan Doyle investigated the scene personally, and wrote up his findings in the Daily Telegraph. He found that the bloody razor was in fact only rusty; that the handwriting expert hired to establish the identity of the writer of threatening letters had made a mistake in a previous case causing the conviction of an innocent person; that the soil on the muddy boots was of a different type than what may be found at the site of the last killing; and that the shirt was hairy due to the fact that it was wrapped up with a piece of horsehide from the dead animal by the police. Finally, Doyle established that Edalji had severe myopia, a sight deficiency that made it virtually impossible for him to carry out the killings at night and doing all that in secrecy. After his investigation, the Edalji case had to be reconsidered and eventually Edalji was found innocent in the killings but guilty in writing the letters. This latter attempt to save face reportedly angered Doyle, but at least as a result, Edalji could practice again. Much later a man called Enoch Knowles confessed to having sent threatening letters for decades in the area. But the influence of Doyle's investigation was not only beneficial for Edalji alone. His efforts drew widespread public attention to the necessity of scientific methods in investigating a crime scene. Moreover, partially as a result of the case, upon realising that no similar office existed earlier, the Criminal Court of Appeal was created in 1907. It seems safe enough to say that Conan Doyle, whose interests ranged all the way from science to the occult, and whose name is remembered today through his creation, Sherlock Holmes, not only contributed to the world of fictional crime writing but also to the investigation of crimes in the real world.

No comments:

Post a Comment